A quick note - the election results went out in email yesterday with two of the write-in candidates reversed. I corrected it as soon as it was noticed, but not soon enough to reach your inboxes. We regret the error.

The police reform bill of 2020 did not pass without its own share of complaints from citizens and the police alike, but of the many reforms it instituted, the one I found the most compelling was the database of officer complaints. The promise, per POST, was a searchable site for the public to see how their officers stack up.

The idea is great for citizens - have a bad experience with an officer? Heck, have a good experience with an officer? Well, let's hop on the POST website and see if this guy has a history of complaints. Or maybe she has no complaints at all! Without a searchable database, the folks who protect and serve are basically unknown to the masses unless you're on the wrong end of the interaction.

It's a great idea, until POST delayed it indefinitely, citing data fidelity issues. Keep in mind, the database form was simple: your local department fills out an Excel spreadsheet with the names of the officers and some additional identifying information, and if there are any misconduct investigations for that officer, they are listed along with the outcome. This data was apparently too complicated for POST, who received spreadsheets from almost 350 departments and then did nothing with them.

Meanwhile, POST was working on another front, officer certification. The idea for POST was to essentially have chiefs of police do recertification interviews with their officers. Kind of easy stuff, too - are you current on your tax payments, have you been subject to a restraining order, have you been sued for being violent toward someone, have you posted anything on social media that could be perceived as racist or sexist, things like that. You know, things I would hope we could all agree our police officers would be able to say "no" without qualification.

(I do wonder how the Millbury cop who showed support on Facebook for the officer responsible for the death of Eric Garner would have answered these questions...)

Well, the police officers union, the New England Police Benevolent Association, felt otherwise, and sued POST over the questions entirely, citing first amendment issues of free speech and association. Injunction granted, and the certification questions get paused.

(By the way, on its merits, I agree with a lot of the broad strokes of the complaint. Whether we like it or not, police can have opinions and associations I might disagree with, but it doesn't make them a bad officer. It doesn't make them a good one, either, but government entities can't police (heh) speech like that.)

The lawsuit is where our story goes pear-shaped.

You'll recall a month ago, where I set out to get all the POST records from the individual police departments, since POST wasn't coughing them up themselves. Around Easter Weekend, I started filing my requests to each municipality in alphabetical order. There are 351 cities and towns in Massachusetts, plus state police and the MBTA Police and the college/university cops, so it was an undertaking. Still, I sent the same email to everyone - send me your spreadsheets and any relevant communications surrounding them.

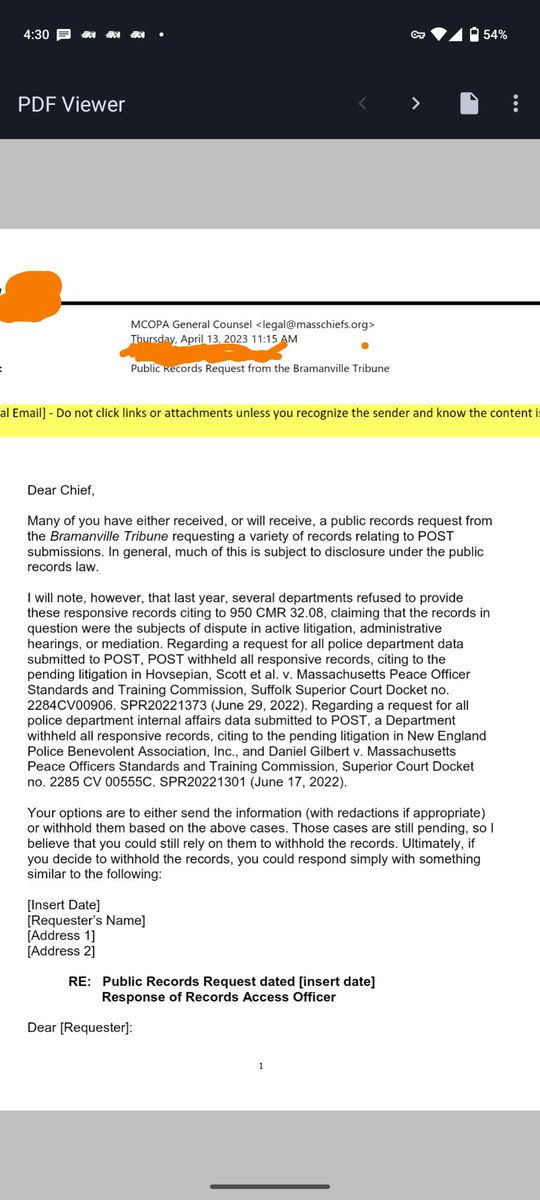

One chief decided to run to the Massachusetts Chiefs of Police Association to find out how to dodge my requests, thus resulting in the image you see above. Eric Atstupenas, general counsel for MCOPA, decided to help them out by providing boilerplate language for chiefs of police and other records officers to use when denying my request:

Although the Department is presently in possession of the requested records, the Department intends to withhold the records in their entirety pursuant to 950 CMR 32.08(2) as the responsive records in question are the subjects of dispute in active litigation, administrative hearings, or mediation. I [sic] support thereof, it is the opinion of the Department that these records relate directly to the matters of Hovsepian, Scott et al. v. Massachusetts Peace Officer Standards and Training Commission, Suffolk Superior Court Docket no. 2284 CV 00906 and New England Police Benevolent Association, Inc., and Daniel Gilbert v. Massachusetts Peace Officers Standards and Training Commission, Suffolk Superior Court Docket no. 2384 CV 00500. Upon review of the information provided on the Massachusetts Trial Court Electronic Case Access, both of these matters appear to still be open and pending. Also, in withholding these responsive records, this Department is relying upon the following decisions rendered by the Supervisor of Public Records in substantially similar matters: SPR20221301 (June 17, 2022); SPR20221373 (June 29, 2022).

Please be advised that pursuant to 950 CMR 32.00 and G.L. c. 66, section 10A(a) you have the right to appeal this decision to the Supervisor of Public Records within 90 calendar days. Such appeal shall be in writing, and shall include a copy of the letter by which the request was made and, if available, a copy of the letter by which the custodian responded. The Supervisor shall accept an appeal only from a person who had made his or her record request in writing. Pursuant to G.L. c. 66, section 10A(c), you also have the right to seek judicial review by commencing a civil action in the superior court.

Yes, the lawyer made a pretty obvious typo in the first paragraph, and that's ultimately what tipped me off. Getting some legalese when making a public records request isn't new. Having the same language flood the Tribune inbox for weeks on end, however, is, and only when I decided to make a public records request specifically asking for communications with that language and that typo did I learn what was going on. Remember, kids, most communications that end up in your chief of police's inbox are public records, and that includes newsletters from advocacy groups.

So what Mr. Atstupenas did was tell these departments that if they cite the lawsuits I mentioned above about the questionnaire, and cite a couple public records request rejections that were upheld by the state that went directly to POST, they'll probably get away with denying me the records, too.

There are many bad parts about this. Most notably, for those observing this and want a reason to care, is how bad the legal advice is.

- Hovsepian and MEBPA, as I note above, are about a questionnaire of no consequence to the spreadsheets.

- The public records request appeals are about POST itself, who are actively in litigation.

- I asked for spreadsheets departments already put together and sent to POST, and any email communications between departments, towns, and POST on how to comply, which are also not about the questionnaire.

I'm not going to slag Mr. Atstupenas too much here, although I did reach out to him and MCOPA for comment and they declined. However, I am not a lawyer even though I know my way around the public records law, and I can tell the difference between a lawsuit about a questionnaire and what I requested. More problematic, to me, is that Mr. Atstupenas is considered a public records expert with the police training organization Municipal Police Institute (aligned with MCOPA) who is spending a significant amount of time helping police departments inappropriately dodge freedom of information requests.

Like, use your powers for good, man! You know appeals will happen, you know this won't hold up under scrutiny - why roll the dice on hoping some intrepid independent journalist will just give up?

...or at least I hope you know, and I think you do, because this week new boilerplate language went out to MCOPA chiefs to try and get me to go away with 8 hours of labor for $75-150 a pop to compile and redact a bunch of records that do not require compiling or redaction. I haven't gotten the language back from the towns I've made the request for yet, but I will soon.

The worst part of it all, though? It's that the police in this state are so afraid of accountability and so angry that anyone would possibly want to know about their interactions with the public that they will go to absurd and comical lengths to avoid it. I'm critical of the police, but I don't think they're all bad like some other abolitionist types do. Given what I've encountered over the last month, however, I can't necessarily blame anyone for holding those sympathies.

For the moment? I'm still plugging away at getting the information from each department; you can see my efforts here. I am sending an appeal to the state for every department that denies me records, and I just hope the state gives out some blanket guidance before they get 200 emails from the Bramanville Tribune that all say the same thing.

More to come, but I've already written too much tonight.

Jeff Raymond is a Founding Editor of the Bramanville Tribune. He can be reached at jeff.raymond@bramanvilletribune.com. Follow him on Twitter at @jeffinmillbury

Member discussion: