Millbury resident Bill Horne, a pioneer in old-time basketball, made professional sports history on three levels.

Born in 1880, Horne was a lifelong Millbury resident and businessman and often worked alongside his father, William, at the Horne and Sons grocery store. He began his sporting career, however, with the Millbury Lits in 1898; the first year of professional basketball. According to the Pro Basketball Encyclopedia, the Massachusetts State League included teams from Hudson, Marlboro, Milford, and Millbury, with Marlboro and Millbury hosting two clubs each.

Millbury's teams held court at the old Town Hall, estimated to hold approximately 900 spectators. Basketball in those days was not quite as high scoring as today's game. In one January battle of the two Millbury teams at old Town Hall, the Lits won by a 2-1 score.

At 6'0", 170 pounds, Horne was big for his day. Yet he was a versatile player too, and he played guard, forward, and center at different times in his career. Scoring picked up as players started to master the game, and Horne averaged 7 points per in his second season.

After a few seasons, Horne moved on to the New England League, where he played for the Nashua, NH franchise. In the NEL, he continued to improve his game - and people noticed. The Boston Globe described him as a “tower of strength” and the Concord Enterprise called him as “rattling player."

Not to be outdone, the Lowell Sun went beyond its competitors in reporting on a performance of his. Horne: “proved very clever in shooting for the basket, and his one-hand throws brought down the house. There has been no such exhibition in the city as was given by Horne last evening… His work was marvelous and the spectators heavily applauded him.”

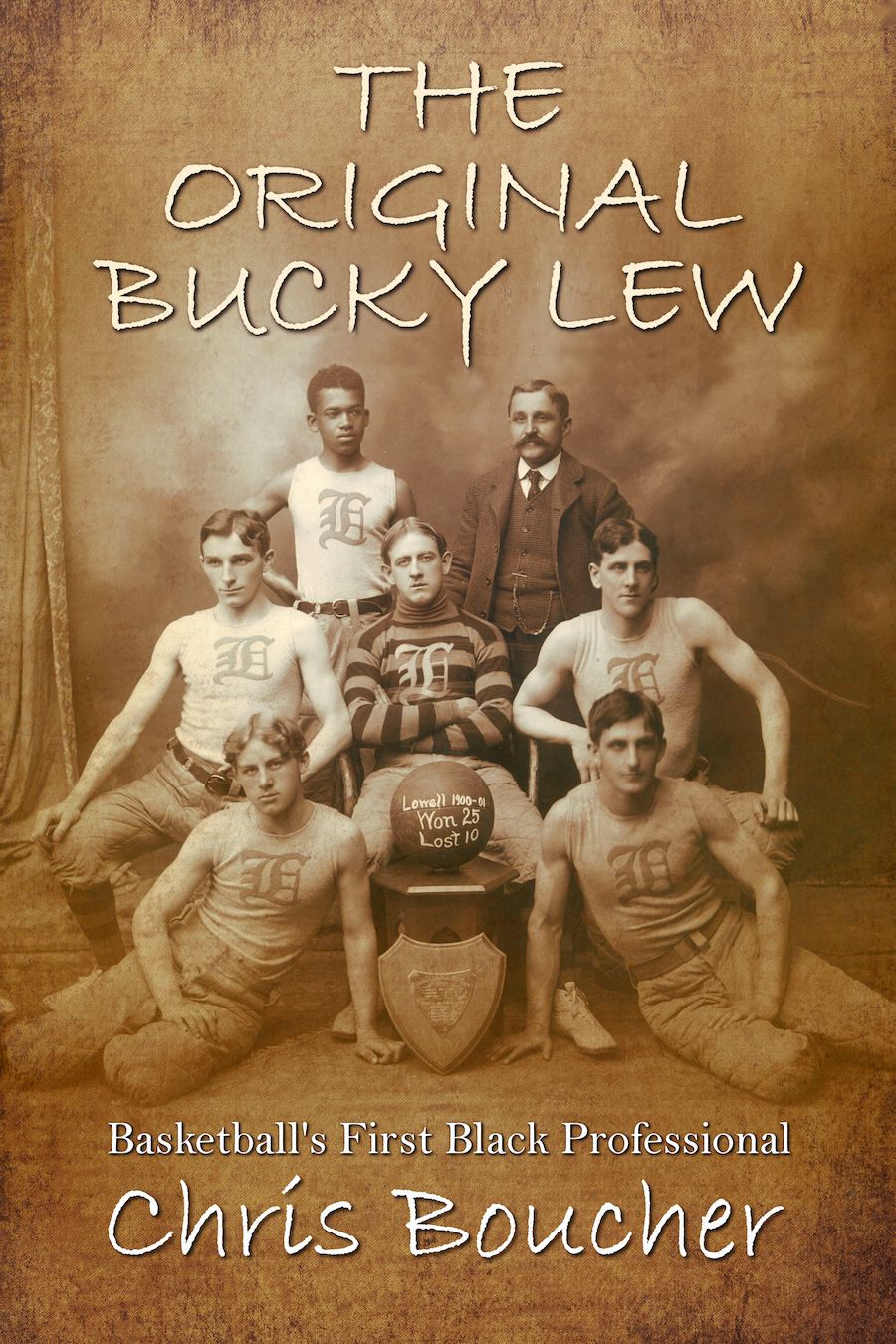

Horne again made history in the NEL; this time, for participating in basketball’s first integrated league in 1902. Harry “Bucky” Lew became basketball’s first Black professional when he took the floor for Lowell that season. Horne played for another team, so while he did not play with Lew, he did not refuse to play him either. That dishonor belongs to the infamous Natick squad, who, led by the game’s best player, Harry Hough, refused to take the court against Lew.

Horne was instead part of the majority of players--silent and otherwise--that supported Lew’s right to play. Ultimately, the league president sided with Lew, fined Natick, and threatened them with expulsion unless they changed course - apparently, Natick decided the color green was more important than black or white because they chose to abide by the league's decision.

The NEL folded after a few seasons and Horne took a 10-year break from professional basketball, likely helping his father run the family grocery store in town. However, when a reconstituted Massachusetts league returned in 1915, he felt the old itch and signed to play with its Fitchburg squad.

There, Horne made history again, this time by playing in the first pro league with integrated ownership. Bucky Lew was now running Lowell’s otherwise white franchise. While all of the leagues in these early days of basketball were transitory, the lasting legacy of open-minded players like Horne is part o their success in integrating professional sports.

Years later, when Branch Rickey and the Dodgers decided to integrate pro baseball, they struggled to find a home for Black players. Their first few calls around the country were poorly received, but when they talked with Nashua Telegraph editor Fred Dobens, they got the answer they wanted. He assured them New England fans would support integration. Roy Campanella and Don Newcombe were placed with the Dodgers minor league affiliate in Nashua in 1946, a season before Jackie Robinson started with Brooklyn in the majors the next year.

Bill Horne died in Millbury in 1966.

Chris Boucher is a writer and amateur historian from the Boston area. His third book, The Original Bucky Lew: Basketball’s First Black Professional, is available at your local bookstore or through Amazon.

Member discussion: