A couple weeks back, I received a text from a friend:

If I've learned anything over the last few years, it's that having one's name popping up on Facebook is rarely a positive. While the accusations of all sorts of nefarious activity and threats against me and my family have largely died down (especially since most of the worst offenders have now directed their attention on a certain murder trial that makes Millbury problems look amateur in comparison), I still dislike the whole Facebook thing these days. It's not just about my personal experience, either - it's one thing to relitigate exhausting debates over allegedly stolen elections or rotaries, it's another to poke one's head in once in a while, see all sorts of toxicity and ridiculousness, and quickly nope back out again.

I get that "I quit Facebook" is the 2020s version of "I don't own a television," but whatever. The amount of time I spent doomscrolling through incessant advertising and unhinged toxicity was not only exhausting, but disturbing. And that's what the attention economy is designed to do - keep you engaged, keep pushing out content to keep you scrolling and hopefully click a few advertisements while you're there. So I opted out of at least the Facebook version of it all.

(By the way, don't come at me with "that's not what happens," because if you haven't seen Meta pushing Instagram Reels with any video content, you're not paying attention, and the Reels/TikTok-style algorithmic behavior is especially pervasive because of the way it trains itself on what you're interested in. It's by design.)

I finally stopped regularly checking Facebook sometime in late 2021, and really only used it from then on to promote community events or activities. I didn't completely nope out on social media. Twitter, for example, is a cesspool of a different type, but is still a valuable news resource and gives you the option of actually seeing what you wanted to follow. Facebook, on the other hand, is just bad. Of the top 10 posts in the original Millbury Facebook group as I write this, one was a Father's Day message from the administrator, four are about Millbury Ave and Howe Ave, one is about doughnuts at Penny Pinchers (which I would have loved to go to had I known), and the rest are advertisements. And if I looked again in ten minutes, it would be a different mix. Meta thinks it knows better than you do, which means if you're trying to connect with people or organizations, you're probably just as likely to succeed by yelling loudly from a bumpout.

What's the point of participating at all?

Cory Doctorow, former editor of Boing-Boing, writer and columnist, futurist, what have you, coined the perfect and somewhat profane terminology for this sort of social media decline: "enshittification."

When economists and sociologists theorize about social media, they emphasize “network effects.” A system has “network effects” if it gets more valuable as more people use it. You joined Facebook because you valued the company of the people who were already using it; once you joined, other people joined to hang out with you.

Network effects are powerful drivers of rapid growth. They’re a positive feedback loop, a flywheel that gets faster and faster.

But network effects cut both ways. If a system gets more valuable as it attracts more users, it also gets less valuable as it sheds users. The less valuable a system is to you, the easier it is to leave...

But as Facebook and Twitter cemented their dominance, they steadily changed their services to capture more and more of the value that their users generated for them. At first, the companies shifted value from users to advertisers: engaging in more surveillance to enable finer-grained targeting and offering more intrusive forms of advertising that would fetch high prices from advertisers.

This enshittification was made possible by high switching costs. The vast communities who’d been brought in by network effects were so valuable that users couldn’t afford to quit, because that would mean giving up on important personal, professional, commercial and romantic ties. And just to make sure that users didn’t sneak away, Facebook aggressively litigated against upstarts that made it possible to stay in touch with your friends without using its services...

When switching costs are high, services can be changed in ways that you dislike without losing your business. The higher the switching costs, the more a company can abuse you, because it knows that as bad as they’ve made things for you, you’d have to endure worse if you left.

tl;dr: Facebook sucks, but we're all stuck there and if you leave, you suffer while the platform also gets worse. If 2024 Social Media was a mall, this is where the "You Are Here" star would sit.

When "enshittification" like this happens, you run into an interesting problem. The Facebook post above is not the only signal I've received that people believe I've disappeared. At a Historical Society event last Thursday, another well-connected, well-known entity in town came up to me and asked me where I had been. This question arose despite my 2024 efforts in presenting at the Historical Society event, organizing a concert for the Friends of the Millbury Library and a Historical Society book talk at Spicy Water, attending no fewer than ten Conservation Commission meetings, assisting in a library book sale, and god knows what else, and that's before my participation elsewhere.

I didn't disappear, folks. I'm just not on Facebook.

If there's one constant throughout the multiple organizations I'm part of, it's that we've utterly lost that sense of communal knowledge. I've watched it in real time; when I started writing my column for The Millbury-Sutton Chronicle in 2017, Facebook had not fully emerged from its "enshittified" cocoon and revealed its abomination of a butterfly. Especially following the national level of conspiracy theorizing about COVID-19 and the 2020 Election, and the never-ending local drama about Rice Road and other town events, we've all split. Heck, it's even apparent on Facebook: I count no fewer than 12 general community groups for Millbury at present.

The biggest flaw, however, is what it does to other forms of connection. COVID exacerbated this, but it's extremely demoralizing to lose touch with people you genuinely care about simply because we all conditioned ourselves to be on Facebook. In the last week, I learned an old friend had twins when I wasn't even aware they were pregnant. Another got married in a small ceremony. Yet another is battling cancer. Why am I only learning this information because I had to open Facebook for something? It's not their fault that I'm not on a toxic platform, but I'm not sure I should be expected to make some Silicon Valley investors richer in order to learn about the life events of friends and acquaintances while sifting through piles of nonsense about Joe Biden's son eating babies off a broken laptop in the basement of a pizza parlor while Vladimir Putin watches, either.

How do we fix this? What do we do? Granted: I am Part Of The Problem(TM) - we tried to launch this project when the Chronicle was sold off, and it's been difficult. I could do more (says the person with a full-time job and wife and kid and mortgage with membership on one municipal board, three community organizations, and anxiety and depression disorders regulated by medication), but it's not up to one person. It's up to all of us. Facebook is a lost cause, because Meta actively does not want us to connect the way we intend to. Local media is decimated. The old ways of connecting people are gone, and aren't coming back. I don't have the answers, and I wish I did.

Have I been a bad friend in that I don't text people enough, don't pick up the phone? I can own that, perhaps. At the same time, a lot of us re-prioritized after the pandemic. I know I'm personally much more forgiving of that sort of thing than I was in the Before Times. But, even seven years ago, we had networks where we were all in the same digital space. Now, we're incentivized to both get away from these toxic platforms designed solely to keep our eyes on advertising and remain on these platforms lest we miss some important information.

And if you do opt out, you get to field questions about where you went, because for some people, if you're not on Facebook, it's like you don't exist at all.

Something has to give. Because, ultimately, the "enshittification" of the very social media applications that promised to keep us all connected? They're also causing the "enshittification" of our entire community.

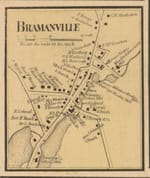

Jeff Raymond is a Founding Editor of The Bramanville Tribune. He can be reached at jeff.raymond@bramanvilletribune.com. Follow him on Twitter at @jeffinmillbury

Member discussion: